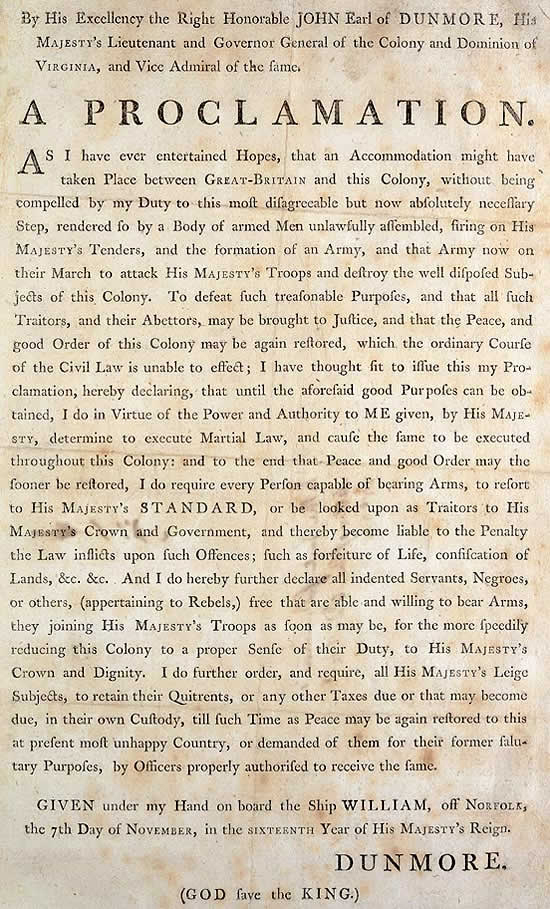

The ten-page manuscript is typewritten, on yellowed legal paper, and folded in thirds. But the words, an eyewitness account of the May 31, 1921, racial massacre that destroyed what was known as Tulsa, Oklahoma’s

“Black Wall Street,” are searing.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top,” wrote

Buck Colbert Franklin (1879-1960).

The Oklahoma lawyer, father of famed African-American historian

John Hope Franklin (1915-2009), was describing the attack by hundreds of whites on the thriving black neighborhood known as Greenwood in the booming oil town. “Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.”

Franklin writes that he left his law office, locked the door, and descended to the foot of the steps.

“The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top,” he continues. “I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?’”

Franklin’s harrowing manuscript now resides among the collections of the Smithsonian’s

National Museum of African American History and Culture. The previously unknown document was found last year, purchased from a private seller by a group of Tulsans and donated to the museum with the support of the Franklin family.

In the manuscript, Franklin tells of his encounters with an African-American veteran, named Mr. Ross. It begins in 1917, when Franklin meets Ross while recruiting young black men to fight in World War I. It picks up in 1921 with his own eyewitness account of the Tulsa race riots, and ends ten years later with the story of how Mr. Ross’s life has been destroyed by the riots. Two original photographs of Franklin were part of the donation. One depicts him operating with his associates out of a Red Cross tent five days after the riots.

John W. Franklin, a senior program manager with the museum, is the grandson of manuscript’s author and remembers the first time he read the found document.

“I wept. I just wept. It’s so beautifully written and so powerful, and he just takes you there,” Franklin marvels. “You wonder what happened to the other people. What was the emotional impact of having your community destroyed and having to flee for your lives?”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/c0/e2/c0e2c3f2-ca2e-4c12-80d2-5b9da3bab69e/20151761001web.jpg)