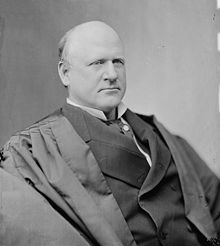

John Marshall Harlan, Associate Justice

1877-1911

In the truly landmark case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts 197 U.S. 11 (1905) Justice John Marshall Harlan, reviewing a $5 fine for failure to consent to vaccination against smallpox, explained for the Supreme Court that it is within the police power of a State to enact a compulsory vaccination law, and it is for the legislature, and not for the courts, to determine in the first instance whether vaccination is or is not the best mode for the prevention of smallpox and the protection of the public health.

That plain statement of judicial deference to elected officials was followed by another that has become the part best remembered, and cited most often in this the moment of the corona virus pandemic:

[W]hen faced with a society-threatening epidemic, a state may implement emergency measures that curtail constitutional rights so long as the measures have at least some “real or substantial relation” to the public health crisis and are not “beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamentallaw.

Coronavirus, Civil Liberties, and the Courts: The Case Against “Suspending” Judicial Review - Harvard Law Review

by Lindsay F. Wiley & Stephen I. Vladeck

In this Essay, we argue that the suspension approach to judicial review is wrong — not just as applied to governmental actions taken in response to novel coronavirus, but in general. As we explain, the current crisis helps to underscore at least three independent objections to the “suspension” model some courts have derived from decisions like Jacobson and Avino. These critiques likewise apply to instances in which courts purport to adopt the appropriate standard of review but do not actually apply it with appropriate rigor.26×

First, the suspension principle is inextricably linked with the idea that a crisis is of finite — and brief — duration. To that end, the principle is ill-suited for long-term and open-ended emergencies like the one in which we currently find ourselves.

Second, and relatedly, the suspension model is based upon the oft-unsubstantiated assertion that “ordinary” judicial review will be too harsh on government actions in a crisis — and could therefore undermine the efficacy of the government’s response. In contrast, as some of the coronavirus cases have already demonstrated, most of these measures would have met with the same fate under “ordinary” scrutiny, too.27× The principles of proportionality and balancing driving most modern constitutional standards permit greater incursions into civil liberties in times of greater communal need. That is the essence of the “liberty regulated by law” described by the Court in Jacobson.28× 28. Jacobson, 197 U.S. at 27 (quoting Crowley v. Christensen, 137 U.S. 86, 90 (1890)).

Finally, the most critical failure of the suspension model is that it does not account for the importance of an independent judiciary in a crisis — “as perhaps the only institution that is in any structural position to push back against potential overreaching by the local, state, or federal political branches.”29× 29. Wiley & Vladeck, supra note 3. Indeed, as Professor Ilya Somin has put it, “imposing normal judicial review on emergency measures can help reduce the risk that the emergency will be used as a pretext to undermine constitutional rights and weaken constraints on government power even in ways that are not really necessary to address the crisis.”30× Otherwise, we risk ending up with decisions like Korematsu v. United States 31× 31. 323 U.S. 214. — in which courts sustain gross violations of civil rights because they are either unwilling or unable to meaningfully look behind the government’s purported claims of exigency...

No comments:

Post a Comment